Without doubt, all eyes in the academic publishing industry are on the Asia-pacific region now. And this is not surprising, as over the last few years, this region has been the centre stage of action in the scientific world, with a steep rise in its research output curve. With the rapidly increasing journal submissions from India and China and with Japan struggling to compete with China, dynamics in the Asia-Pacific region are changing.

Let’s get down to the facts first. According to the 2012 Nature Publishing Index (NPI), 13 institutions in the Asia-Pacific region have been ranked among the top 100 scientific institutions globally. While Japan still has the leading position in this region, with six institutions in the top 100 list, the figure has gone down from seven Japanese institutions in the list in 2011. On the other hand, China has four institutions, up from three last year, while Singapore is a new entrant on the top 100 list. South Korea no longer figures in the list.

What is even more disconcerting for Japan is that five of the six institutions in the top 100 have fallen in the global ranking. For instance, Tokyo University has dropped from the sixth to the ninth position, Kyoto University from 20th to 25th. Todai or Tokyo University, which has consistently been the top name in Asia-Pacific science, is now vying for supremacy with the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). In fact, in early 2013, CAS went ahead of Todai marginally. Will Todai be able to maintain its position throughout the year? Or will CAS be the new lead in Asia-Pacific?

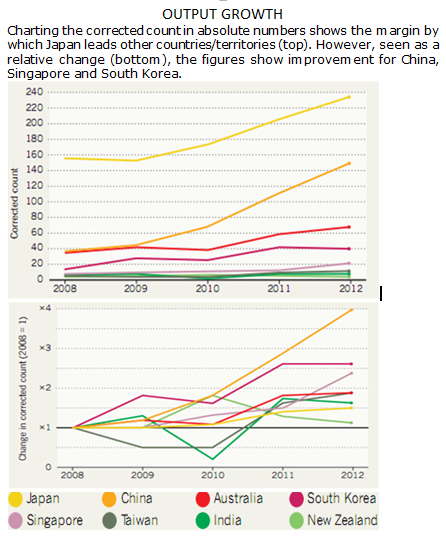

In terms of scientific research output, China, Singapore, and India are on the rise. Japan has seen only a modest increase of about 55% in output in the past five years, while China has increased its publication count by 300% over the same period of time. Over the last decade, India has achieved an 80% growth in research output. Singapore and Taiwan are also rising fast.

Source: Nature Publishing Index 2012 Asia-Pacific, page 9

The main reason for Japan’s declining curve is shortage of funds for research. The country is still recovering from the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. Understandably, a large proportion of government funds and resources have been diverted towards reconstruction. As with most other developed economies, Japan is still coping with the economic downturn. From 2008 to 2011, Japan’s economy shrank by 10%. Consequently, funding sources for scientific research in Japan are under severe constraints. Gross domestic expenditure on research and development (GERD) as a proportion of GDP also decreased from 3.5% in 2008 to 3.3% in 2010, which made spending on scientific research even more difficult.

It is not all bad news for Japanese science though. The country still has 80 universities in Asia-Pacific’s top 200. Japan also holds regional first place in three of the NPI’s subject categories (chemistry, life sciences and physical sciences) and ranks third in earth & environmental sciences. Of course, China’s large population and economy are supporting the growth in Chinese science. But, as a percentage of its population, China has fewer researchers than other Asia-Pacific countries. Also, according to a recent report by Thomson Reuters, the perceived impact of published research, as measured by the number of citations per article, tends to be lower for China than for Japan.

The need of the hour is to find alternative funding sources. With government money tight, Japanese universities have been examining other potential funding routes. There are many Japanese research areas into which foreigners might see value in investment. However, Japan really needs to act fast if it wishes to hold on to its position by the end of this year. It is up to the Japanese scientific fraternity to prove that they are still the best in Asia-Pacific.